On 21. November 2014 I gave a talk on “(Re-)producing National Borders in Everyday Life” at the workshop “Living in European Borderlands“, organized by the research project “Cross border residence. Identity experience and integration processes in the Greater Region (CB-RES)” at the University of Luxembourg in Walferdange.

As it gives an English language insight into one very interesting strand of argument of my dissertation on the “The Everyday Reproduction of National Borders” (“Die alltägliche Reproduktion nationaler Grenzen“, UVK, 2014), I’d like to share it with you. You can either download the slides with extended notes as PDF or just read on.

The underlying hypothesis of much of border studies seems to be that the formal opening of national borders should instantly lead to rich cross-border interactions. Still, empirical research shows how little of this is actually happening. The research question derived from this most of the times is: “Why is there so litte cross-border interaction, although the border has been opened?”

In this presentation I will start by asking kind of an inverse question: „Why should there be cross-border interaction in response to a political border opening?“ This question focuses not on the reasons for immobility but on the preconditions of actual change in the everyday behavior of people living in borderlands.

This research question leads us to three general theoretical concepts we have to develop before we can talk about the specific question:

- How do we conceptualize space?

- How does everyday behavior change?

- How does change in spatial structure change everyday behavior?

In recent years, social space probably has been one of most widely discussed basic terms, especially in term of its social constructions. Its formative dimenson for people’s cognition and behavior has meanwhile been neglected a litte bit.

For my research I decided to utlilize an established concept of space that has been developed by geographer Dieter Läpple in a 1991 essay: Läpple suggests understanding „space“ as a configuration of four dimensions: a physical substrate of topography and artifacts, patterns of (inter-)action on top of this substrate, rules and regulations governing these interactions and, finally, symbols and signs loading those with meaning and significance.

If we take this concept, we can now ask how the border opening in Europe can be understood. In its core, is has to be considered a change in the rules and regulations governing not only Europe as a whole, but especially the border regions where the opening of the borders instantly effects local spatial structure.

There is no immediate effect of the act of implementing the Schengen Treaty in any of the other dimensions. Effects in other dimensions can originate in the rules and regulations but they have to be mediated by some social mechanism.

Now, let’s have a look at the second theoretical concept: everyday behavior. I will not refer to an understanding based on rational decision making, but a pragmatist understanding of everday behavior as „chains […] of actors confronting problem situations and mobilizing more or less habitual responses“ (Gross 2009, p. 268).

Those routines are developed in the interaction between the opportunities present in the spatial structure and an actors beliefs and way of seeing the world (Hedström 2008).

Even though routines are relatively stable, change can originate in the opportunities or the beliefs of a person. If an opportunity that has formerly been utilized disappears, the person has to find a different way of solving her everday problem. Newly emerging opportunities might make a person become curious, try them out and slowly change his established routines, but they by no means directly induce change into everyday routines!

Finally, beliefs are reflexively monitored by people allowing them to slowly change their course if there is a mismatch between beliefs and new information acquired by a person.

Now, all conceptual building blocks are in place so we can have a look at mechanisms that could mediate change in the patterns of (inter-)actions originating in the rules and regulations of spatial structure.

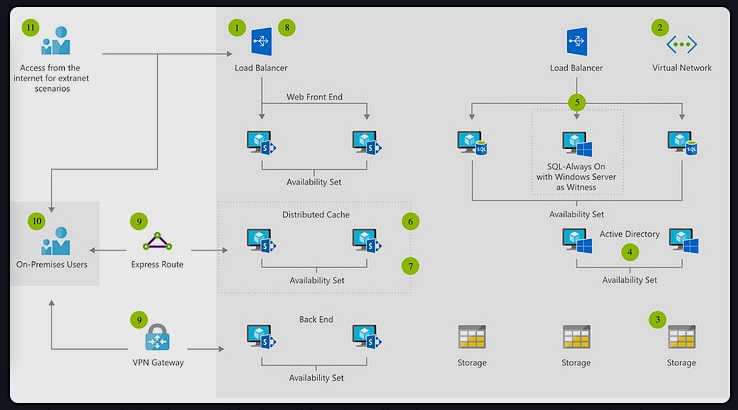

The diagram shows how cross-border routines could emerge in reaction to a border opening. We can see now, why this change happens so slowly: a border opening opens up new opportunities which, as we have just seen, do not directly induce actual change in routines!

Rather there need to be specific incentives or mismatches in an actors beliefs for routines to change. Even worse, those beliefs are only very indirectly coupled to formal rules and regulations.

The mechanism that actually dominantes in border regions can be seen in this diagram. It emphasizes that people simply continue to do what they have always done, as there is no reason for them to deviate from their established routines.

These theoretical considerations have been derived from about thirty interviews conducted in three German border villages. These are directly adjacent to a much bigger city located on the other side of a national border (or in one case former national border).

Here people can easily include the attractive neighboring city into their everyday lives as they are only a few minutes away, by bus, by car or even by bike or on foot, putting them into people’s pocket of local order (Hägerstrand 1985).

For different areas of everyday life there are specific mechanisms how beliefs – and thereby routines – change.

„Serious“ and „casual“ leisure refer to a distinction made by Stebbins (2001), where serious leisure includes activities that capture a person “with complexity and many challenges” (p. 54), while casual leisure refers to pastimes with little emotional involvemet like watching TV or taking a walk.

As you can see in the diagram, there are very specific characteristics that influence how everyday routines in this area might change. Those have to be taken into consideration when explaining the change in a specific border region.

The three border regions of this study showed how there needed to be a trigger for people to extend their activities across the border: either some social connections or an interest that could not be sufficiently fulfilled on the own side of the border.

The factors relevant for casual leisure are different from serious leisure. They seem much more susceptive to changing routines and, in fact, this is confirmed by the empirical data collected in the three border villages.

While borderlanders often have a walk in the neigboring city or make use of zoos and the bicycle infrastructure, the language barrier makes them rarely visit the theater or the cinema, which they prefer doing in their home country.

Food shopping is again shaped by another set of relevant factors: There is curiosity and a desire for some goods that are only available in the neighboring country. Still, most of the food shopping is done in the big supermarkets directly in the border villages or on the way to or from work – for cross-border commuters as well as for those communting nationally.

This presentation has shown how, from a mechanismic perspective, the lack of cross-border interaction in borderlands is little surprising.

There are very special mechanisms that shape how routines change, allowing cross-border routines to develop. When researching cross-border interaction it is necessary to consider precisely in which dimension of spatial structure the change is happening. Spill-overs into other areas are possible, but a mechanism has to be proposed on how this spill-over might happen.

For encouraging cross-border interaction, much more effort needs to be put into actively creating mismatches in people’s beliefs, sawing seeds for the emergence of cross-border everyday routines.

Additional references in the notes:

Hägerstrand, T. (1985). Time-geography: focus on the corporeality of man, society and environment. In United Nations University (Ed.), The Science and Praxis of Complexity (pp. 193–216). United Nations University.

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Serious leisure. Society, 38(4), 53–57.

Der Beitrag Talk: “(Re-)producing National Borders in Everyday Life” erschien zuerst auf nilsmueller.info.